The War for Attention

Education is a pillar of society, one that many people have claimed has been eroding over time. The erosion, many people feel, has come from the following sources: technology, a chronic institutional failure on the part of our education system, a decline in the importance of family, but most importantly; a sentiment of wide-scale apathy. Apathy is defined as a lack of interest, enthusiasm, or concern. The subject matter of antisemitism and the events that took place during the Holocaust are not immune to this cancer of complacency. The questions that people with influence should ask: “Why are people so apathetic?” and “What can we do about it?” The answer to those questions seems to have been realized.

Epistemology or the theory of knowledge, attempts to tackle the question of how we know what we know and why do we know it? A simple question that may have eluded people is, “why do we know anything?” That question may appear self-evident, but if you give it a second thought, you may realize that the reasons that we know the facts that we do has little to do with what is important. In a perfect world, perhaps then we would prioritize our knowledge based on the importance of the information. For the doubting readers, I can provide examples of exactly what I mean: there are people (adults) in this country that can identify reality tv stars but cannot name our Vice President. Some people know the entire history of sports teams; all the players, all the coaches, and every statistic involving their team, but they cannot perform basic arithmetic. Lastly, some people do not believe that the world is round! They hold this belief despite the overwhelming evidence of the contrary.

It would be quite easy to write those whom I have mentioned off as “stupid” or “uninformed.” As both an educator and a student, I want to know how these contradictions can exist. Belittling these people’s intelligence would not fix anything and we might be wrong to pass judgment. Consider the mathematical talent it would require for someone to harbor the encyclopedia of sports knowledge that many “stupid” Americans hold. How could anyone be labeled uninformed when they go out of their way to concoct conspiracy theories that can get so outlandish that they invoke the usage of several sciences? Granted, their sciences are often cherry-picked or misused, but there is an attempt afoot. There is a concern, an interest, and a sense of enthusiasm that cannot be denied.

Why then should history be any different? Historical information is readily available in classrooms, libraries, and museums across this country, and yet there are gaps in people’s knowledge about objectively critical information. The issue with not knowing something is; that you do not realize that there is a vacancy in your knowledge until it is exposed. Going back to the prominent question at hand, “Is using fiction to study the history a legitimate methodology or not?” The answer appears to be “Yes!” Fiction can be used to introduce a topic about which you did not know. That resolves the issue of identifying what you do not know. But what about the apathy issue? Fiction is a methodology that resolves that matter as well.

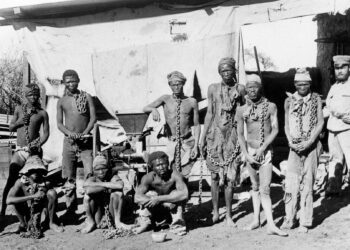

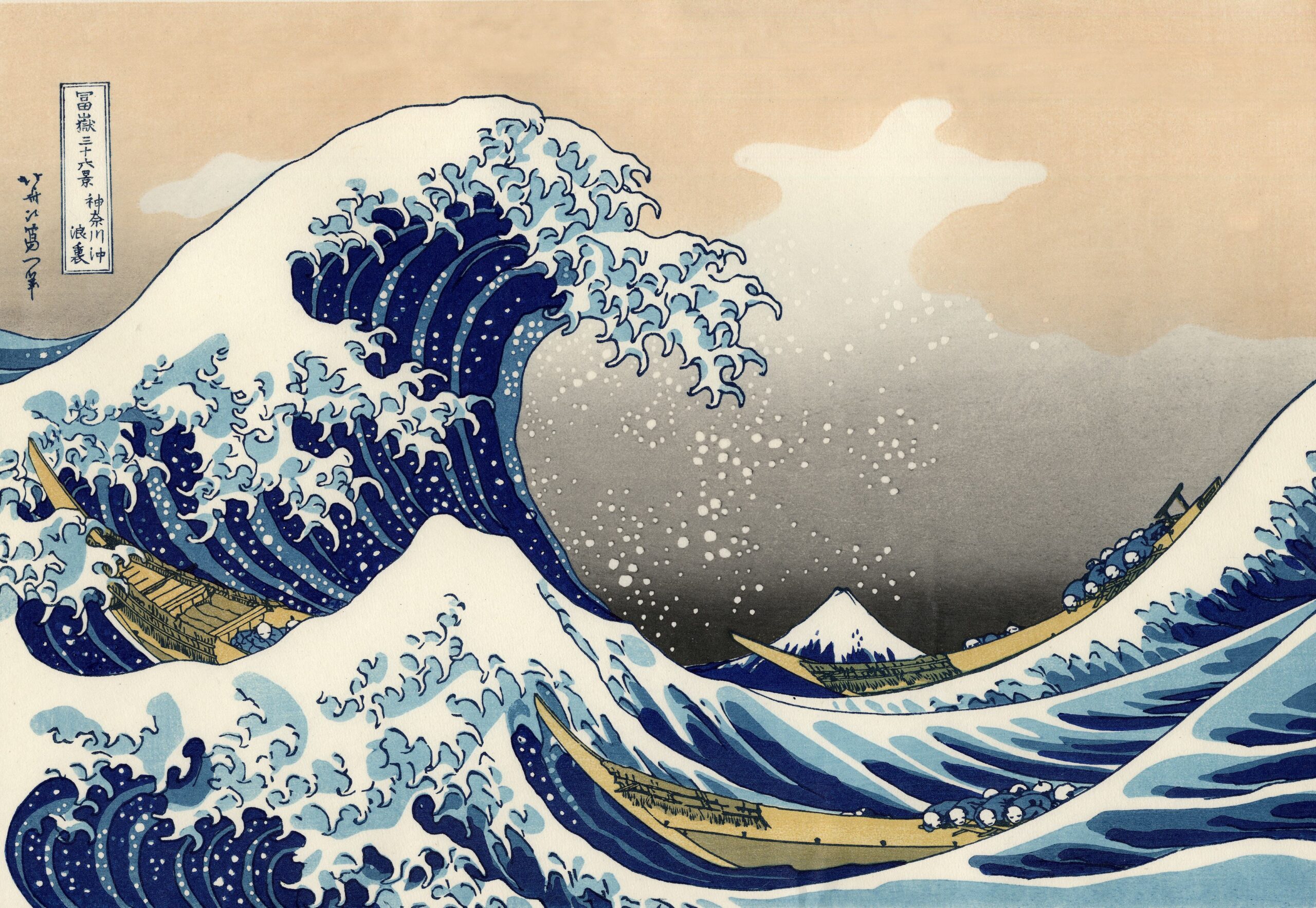

If the story is told correctly and with some level of entertainment, then people will listen, and they may even learn. A dry reporting of events has a tough time competing for modern people’s attention when they have smartphones readily available to them and access to compelling and time-consuming media like video games, television, or the internet. The story must be meaningful, it must be confined to a reasonable amount of time for consumption, and the audience must be able to understand it. Examples may include The Last Samurai, Gladiator, Roots, and the television series, Holocaust. These examples are technically fiction, but they are telling a story that is based on truth. Japan did struggle with modernization in the Meiji restoration era, slavery in America did happen and the impact has lasted for generations, and the Romans did have a system in which slaves were forced to fight to the death for people’s entertainment.

Regarding the series Holocaust, the controversy was risen when Elie Wiesel, a real Holocaust survivor, took issue with the series. Wiesel wrote to the New York Times in 1978 with a litany of criticisms many of which were correct. Wiesel wrote “Why is the series called ‘Holocaust?’ Whoever chose the name must have been unaware of the implications. Holocaust, a TV spectacle.” Wiesel continued to berate the creators of the made-for-TV series because the characters experienced too many things at once. As a living survivor of the tragedy, his voice should be heard and we should take into consideration, the feelings of those who experienced the events. It is also true, that we owe it to those very people, to not forget what happened to them. For that reason, we must overcome apathy and create sources of information that are informative, available, and engaging.

The level of understanding that we expect may not be realistic. The common person is not going to be a scholar on every subject. That demand is unrealistic. What we can do in society is, we can prioritize information that we deem to be vital. The Holocaust is such information. We can then take that subject and focus on the important aspects of it, antisemitism, the ghettos, the death camps, and so on. Then, we can create a curriculum that has ease of entry, one that is available for most people. A program that can be completed in a reasonable amount of time, filled with facts, and plot devices that move the story to keep the audience engaged. The curriculum that I am referring to could be articles of fiction. The series Holocaust is a perfect example. It is short enough to be consumed, it was published on television which means it is low in cost, it keeps the viewer engaged, and it is filled with factual information.

Fiction like Holocaust the series may lead the unaware student to pursue the topic. These future students may then change their source of education from television to the university. The fiction, in this example, is generating interest and it answers these simple questions, “why do we know anything?” and “how do we overcome apathy?” We know things because we are interested, and we overcome apathy by creating interesting and consumable narratives that engage people. Returning to the question of epistemology. If we were to poll the people that I referenced earlier, about slavery in America, the Samurai, or the gladiators of Rome, I would suspect that those “stupid” people, would know something about those topics. That means, that the entertainment value of fiction was able to penetrate their apathy and they did learn through fiction.

If you are not convinced, then let us explore the opposing view. Let us assume that those who claim that fiction is not a legitimate methodology for studying the Holocaust or any historical subject matter. If that is true, why do people have a greater knowledge of the events in WWII over WWI? If the answer is because WWII is closer in time to the modern-day, then why do people know more about the Roman gladiator Spartacus than they do about abolitionists like John Brown? The answer is that people do not have an interest in John Brown, but they do in people like Spartacus. There is vastly more information about John Brown, an American from the nineteenth century than there is about a Roman gladiator who died in the year 71 BC. The prioritization of information is not based on how valid it is to the individual’s life nor is it based on when the events happened. People learn things because the information is available and engaging. Using fiction makes information more available and easier to consume.

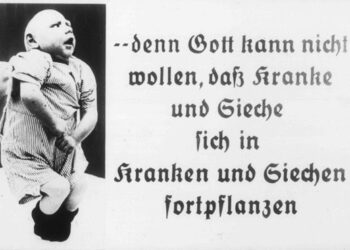

The subject matter cannot be ignored, the Holocaust is an exceptionally dark chapter in history. As a society, we tend to want to shield the youth from horrors like genocide. The darkness of the subject is the very reason the story must be told, even to our teenage students. Through this exposure, we may inoculate our youth from the terrors of reality. There is however a difficulty in finding material that would be appropriate to use in the classroom without the objection of their parents. An objection that may be legitimate. Again, fiction is the answer.

Movies like The Great Dictator are perfectly acceptable to be shown in a modern classroom. The objection one may have with the film is the age at which it was produced, but otherwise, there is an ample amount of content to illustrate antisemitism. The film is a comedy, and it is the use of humor that keeps the students engaged, but there is a deeply profound message underlying the story. Yes, Holocaust survivors like Elie Wiesel may indeed find issues with antisemitism being displayed as a comedy but Charlie Chaplin justifies his potentially insensitive work with his final speech. A speech that was meant not only to bring peace to the characters in the film but also to enlighten the respective audience. The clumsy Barber who happens to be mistaken for the film’s reimagining of Adolph Hitler says: “I am sorry, but I do not want to be an emperor. That is not my business. I do not want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone – if possible – Jew, Gentile – Black man – White…” Hitler would never forfeit his power and appeal to humanity; so clearly this is fiction. The meaning behind the words is what is important. The respective viewer sitting there watching should realize that what the character on the screen is saying is true and what the real man said is not. In this example, fiction is telling a greater truth than nonfiction at the time, which was failing to express. There are examples that historians can turn to and say that people back then had all the information that they needed to be informed, but the information is useless if those same people are not exposed to it. Fiction is a methodology to expose that information to common people.

If we have topics that we deem to be so important that we require every man, woman, and child to become a repository of facts about them, then we must realize that there are barriers that need to be dealt with. The average person is not going to watch a documentary like Shoah, a nine-hour series of interviews filled with facts about the cruelties of the Holocaust. For many, such material is unwatchable or at the very least, “Inaccessible.” It is true, that Shoah, is filled with facts, but that does not matter if people do not take the time to watch it. People could watch the series Holocaust, with all its flaws, and then gain interest in the subject. Then they would consider watching Shoah and pursuing a higher level of education on the subject. The usage of archetypes works so well because they are identifiable. Narration devices like irony or foreshadowing, keep the intended audience engaged. Through this engagement, we can overcome apathy and answer the epistemological question. There are great truths that reside in fiction. Like Shoah, “Never Again” does not mean anything if people do not know what happened. Mary Poppins was on to something when she said, “A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down.” The medicine will not work if you do not take it and fiction may be the sugar we have been looking for.

References

Berger, R. (Producer), Chomsky, M.J. (Director). (1978). Holocaust [Television Miniseries]. West Berlin & Austria: NBC Broadcasting Company.

Chaplin, C. (Producer), Chaplin, C (Director). (1940). The Great Dictator [Motion Picture]. United States: Charlie Chaplin Productions

Haley, A. (Producer), Chomsky, M.J. (director). (1976). Roots [Television Miniseries]. United States: ABC Broadcasting Company.

Walt, D (Producer), Stevenson, R (Director). (1964). Mary Poppins [Motion Picture]. United States: Walt Disney Productions.

Wick, D (Producer), Scott, R (Director). (2000). Gladiator [Motion Picture]. United States: Universal Pictures

Wiesel, E. (1978, April 23). TV VIEW. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/1978/04/23/archives/tv-view-in-defense-of-holocaust-defending-holocaust.html.

Zwick, E (Producer), Zwick, E. (Director). (2003). The Last Samurai [Motion Picture]. United States: Cruise/Wagner Productions

Courses

Courses America and the World

America and the World East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present

East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies