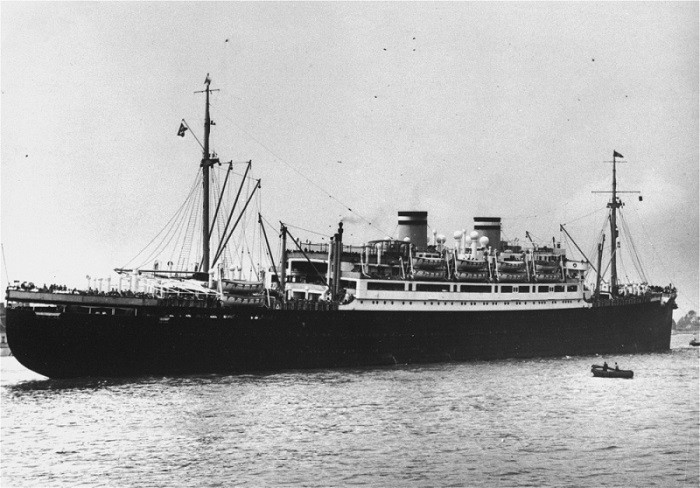

First, it is obvious to say that things would have been better for the passengers aboard the St. Louis if the United States just accepted them. The consequences would have undermined the concept of visas, immigration quotas, public opinion, and representative government; but it would have been a better outcome for the Jewish refugees. As Peter Hayes describes in his book, Why: Explaining the Holocaust, “Of the 937 Jews on board, 28 got off in Cuba, and one committed suicide. Of the 908 remaining, 620 were admitted to France, Belgium, and Holland, where 365 survived the war. Britain admitted 288, all of whom were similarly fortunate. In short, about three-quarters of the once apparently doomed passengers in fact found secure refuge from the Germans, and about half eventually found their way to the United States.” (Hayes, 273). Had the United States accepted these refugees, roughly 255 Jews that were murdered by the Nazis, would have lived; while the others would have been freed from the tyrannical Nazi war machine that swept Europe in the years that followed.

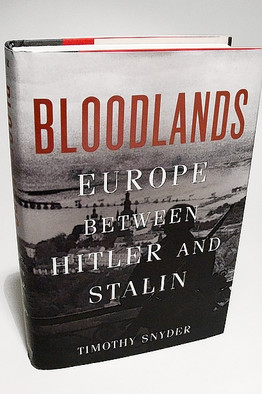

Second, context and geography are important when discussing international obligations. Timothy Snyder writes in detail about how the Soviet Union was systematically killing its citizens throughout the 1930s in his book, Bloodlands. Snyder writes, “Once a large number of Polish suspects had been gathered in a single place, such as the basement of a public building in a town or village of Soviet Ukraine or Soviet Belarus, a policeman would torture one of them in full view of the others. Once the victim had confessed, the others would be urged to spare themselves the same sufferings by confessing as well” (Snyder, 95). Many of those Poles mentioned were Catholics and Jews. Moreover, Hayes references that the policy of Eastern Europe at the time was unfriendly to the Jews. This should be no surprise since the Eastern Europeans have never been fond of the Jews. Hayes writes, “At the meeting of the Council of the League of Nations in May 1938, Poland and Romania explicitly expressed the desire to reduce the size of their Jewish populations and requested aid in doing so. The following October, Poland’s ambassador in London tried to blackmail Britain into allowing 100,000 Polish Jews into its colonies per year by stating that otherwise his government would be ‘inevitably forced to adopt the same kind of policy as the German government’” (Hayes, 265). Eastern European countries rejected their moral obligations to help those in need. Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union are much closer geographically and culturally to the Jews of Europe in the 1930s, yet they shirked their responsibilities. Typically, refugees are the burden of nearby countries, for the Jews of Germany that would be France, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union, and the Baltic region. Of these choices, one would consider the Soviet Union as the most capable of rising to the occasion; especially considering the rhetoric that the Jews were somehow in league with the Communists. By the 1930s, that was surely not the case. The Soviets only accepted Jews that were sympathetic to the Communist cause; those who were not “corrupted” by Capitalism. The Soviets would only accept Jews that were willing to subject themselves to manual labor and forfeit their religion. (Hayes, 262). In other words, the Soviet claims of equality and diversity were simply propaganda.

That leaves the Jewish refugees in the hands of Western Europe. There are conflating figures as to which country took how many Jews based on the year. Since the discussion is on the St. Louis in 1939, it is apparent that only numbers going to 1939 are relevant. By 1939, Holland took in 23,000 – 30,000 Jews, Belgium accepted 30,000 Jewish refugees, and the French received 50,000 Jewish refugees (Hayes, 260-2). The British, who were further from Germany, took in roughly 60,000, which was a number higher than their immigration policies allowed (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk). In contrast, Hayes reports that the United States’ numbers were not only higher than those of the Jewish neighbors in Europe, but the United States accepted the most refugees even as early as 1939: “From all of Europe in this interval, the United States took in only 92,000 Jews. If one extends the time frame to 1933–44, the immigration total for America is probably about 225,000 Jews from all of Europe…” (Hayes, 266). The United States accepted more Jewish refugees than any other country between 1933-1939 and between 1933-1945, despite the fact that the United States is across an ocean and was not involved in World War II until 1941. All the while, the Canadians received no more than 5,000 Jewish refugees by 1939; the Canadians did eventually take in 50,000 in total but in 1939, they rejected more Jews than any other Western nation; including the passengers of the St. Louis (Hayes, 263). However, the USHMM does not mention these facts, and no one seems to question the moral failure of the Canadians on this matter. On November 7th, 2018, the Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau apologized for the failures of his government that occurred in 1939, generations before he was born(CBC).

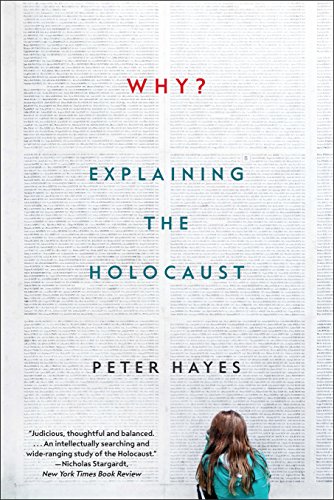

The Jews of Europe faced discrimination in their neighboring countries and even abroad in the United States, Cuba, and Canada. The terms used for these refugees were “burden” and “problem.” The antisemitic rhetoric from the likes of Adolph Hitler is known and their stance on the Jews being a “problem” is well established. But why were the Jewish refugees considered a “burden?” The Jewish refugees were stripped of their wealth prior to fleeing Europe, leaving them destitute, a condition in which any nation that sought to provide asylum would also take up the financial “burden.” The United States, claims to be a country “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” In this case, the people did not want more immigrants after the Great Depression. Especially immigrants that were German; that were not Protestant, that would need financial support, and especially immigrants that would displace the successful business owners and skilled laborers. Hayes reminds us that FDR was a friend to the Jews and that even he was limited in what authority he had regarding the Nativistic populace (Hayes, 269).

Antisemitism is a sophisticated form of nativism, in which it is difficult to identify one from the other. In some cases, antisemitism is clearly separate from basic nativism. For instance: “Given such attitudes, perhaps one should not be surprised that a poll in 1938 found that 58 percent of Americans considered Jews in Europe at least ‘partly’ at fault for their own persecution … Another survey in July 1939 showed that 32 percent of Americans believed Jews had too much influence in business, while another 10 percent favored deporting Jews. The prevalence of these views caused even the proponents of helping Jewish refugees to sanitize their vocabulary and to speak of ‘persecutees’ who needed help, not of Jews” (Hayes, 269). These polls clearly reflect that United States citizens were largely antisemitic in the 1930s. Like the citizens of Germany, Americans are humans, and they are subjected to manipulation. Antisemitic orators were in no short supply in this era: the Irish Catholic, Father Charles Coughlin expressed antisemitic views through radio broadcasts that influenced Catholics (Hayes, 269). The aviator, Charles Lindbergh accused the British, the FDR administration, and the Jews of stoking the fires of war in his speech Who Are the War Agitators? In short, there was an abundance of antisemitism, even in the United States. While it is true that Americans were suspicious of Jews and many were antisemitic, as stated, nativism and antisemitism are difficult to separate. “For example, the dentists of Westchester County lobbied FDR’s political advisor Samuel Rosenman to prevent the admission of any more refugee dentists into the country, and the national conventions of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion passed resolutions against further immigration so long as unemployment persisted in the United States. Such resistance resulted in strict enforcement of the Likely to Become a Public Charge, or LPC, rule, which denied immigration to people considered so lacking in funds that they would become dependent on welfare” (Hayes, 268). Perhaps, the Dentists of Westchester County and the Veterans were antisemitic, or maybe they were just nativists concerned with the economy and preserving their jobs? In either case, the outcome for the Jewish refugees was the same.

Times have changed from the Nazi era. The traditional view that “what happens in another man’s country is not my business” has surely faded. While the United States was guilty of Nativism, isolationism, and Antisemitism in the 1930s, it is now recognized as the “World Police.” As President George W. Bush said when he addressed the nation and the world after the terror attacks on September 11th, 2001, “My fellow citizens, the dangers to our country and the world will be overcome. We will pass through this time of peril and carry on the work of peace. We will defend our freedom. We will bring freedom to others, and we will prevail” (President Bush Addresses the Nation). The United States will no longer sit silently as a bystander to the evils committed abroad. Recent history has proven that “inaction is action,” While it might be difficult to relate the politics of the Conservative, George W. Bush; the Progressive Senator Joe Biden (in 1995) expressed his belief that “there is no moral center in Europe!” when he addressed the Congress in 1995 regarding the Bosnian genocide (USA: WASHINGTON: SENATE APPROVES US TROOPS DEPLOYMENT IN BOSNIA). Unfortunately, despite the good intentions of the United States and its intervention on the global stage, there are still those who enjoy pursuing the line that the United States is an evil and Racist country. The only proof that one needs to refute such claims are the words from countless Jewish refugees like Frank Cohn who ends his Eyewitness testimony of the Holocaust, saying “God Bless America” (Eyewitness to History: Holocaust Survivor Frank Cohn).

Bibliography

Biden, Joe R. “USA: Washington: Senate Approves US Troops Deployment in Bosnia.” YouTube, July 21, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwYVKptqH_o&ab_channel=APArchive.

Bush, George W. “President Bush Addresses the Nation.” National Archives and Records Administration, March 19, 2003. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/iraq/news/20030319-17.html#:~:text=My%20fellow%20citizens%2C%20the%20dangers,others%20and%20we%20will%20prevail.

Canadian Press. “Trudeau to Apologize Nov. 7 for 1939 Decision to Turn Away Jewish Refugees Fleeing Nazis | CBC News.” CBCnews, September 6, 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/justin-trudeau-st-louis-november-seven-1.4813667#:~:text=On%20November%207%2C%20the%20Liberal,Jews%20fleeing%20the%20Nazi%20regime.

Cohn, Frank. “Eyewitness to History: Holocaust Survivor Frank Cohn.” YouTube, July 13, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DMB3on46bCQ&ab_channel=UnitedStatesHolocaustMemorialMuseum.

Hayes, Peter. “Chapter 7: ONLOOKERS: Why Such Limited Help from Outside?” Essay. In Why?: Explaining the Holocaust, 259–99. W.W. Norton and Company, 2018.

Lindbergh, Charles A. “Who Are the War Agitators? The Fight for an Independent Destiny and American Neutrality in World War II.” Speech, September 11, 1941.

Snyder, Timothy. “Chapter 3: National Terror.” Essay. In Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin, 89–117. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2022.

The National Archives. “Kindertransport.” The National Archives, December 17, 2018. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/kindertransport/.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Confronting the Holocaust: American Responses.” YouTube, February 18, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMTPAE53PqE.

Courses

Courses America and the World

America and the World East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present

East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies