Anti-Semitism: The Ancient Excuse

“In Polná, at century’s end, the victim was older than usual, a nineteen-year-old woman, but the rest of the story conformed to the script: at Passover time, villagers discovered a body. The throat had been slit and the body drained of blood. Near the body, townsmen found a knife said to be used in the kosher slaughter of animals; shortly afterward, a renegade or disreputable Jew corroborated the accusation. Sadly, in this case, the falsely imprisoned Jew, Leopold Hilsner, having been threatened with lynching in jail, confessed to the murder to avoid being strung up. He retracted the confession in court but was convicted nonetheless and sentenced to death, later commuted to life in prison.”[1]

Examples of antisemitism are cited regularly throughout history, whether it be in The Bible, in medieval Europe, after the Enlightenment, during the Holocaust, during the Cold War era, or even today. It is believed that antisemitism began with Judas Iscariot’s betrayal of Jesus Christ, the violation that led to the Romans torturing the Christian Messiah to death.[2] The Christ Killer excuse is not the source of antisemitism, because the Jewish people were oppressed long before Jesus Christ; however, it is an excuse that many throughout history have used to rationalize their hatred.

The Christ Killer excuse is one of the earliest recorded times that the Jewish people would be scapegoated, but not the last. A trend that can be found throughout history, when in doubt, blame the Jews. Even the Black Death, was blamed on the Jews. “In 1348 there appeared in Europe a devastating plague which is reported to have killed off twenty-five million people. By the fall of that year, the rumor was current that these deaths were due to an international conspiracy of Jewry to poison Christendom.”[3] The claim that the Jews were responsible led to the Strasbourg Massacre in which several hundreds of Jewish people were publicly burnt to death on February 14th, 1349, and the rest were expelled from the city.[4] The theme of conspiracy continues throughout history to this very day. One would think that in modern times, people would not be subject to such paranoia. Charles Lindbergh, a famous anti-Semite, once claimed that the Jewish people were manipulating the government and the entertainment industry with the goal of programing the American people to want to participate in World War II. The objective would be to liberate the Jewish people from the Nazi regime that swept across Europe. In the article, Who are the Agitators? Lindbergh wrote, “Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, and our government.”[5] Through these historical accounts, it becomes obvious that there is an acceptable amount of antisemitism throughout the public discourse. If antisemitism were not in ample supply, one would think that people like Lindbergh would not be so bold with their bigoted claims; claims like the Jewish people were actively trying to poison and kill Christians and that they were manipulating citizens to go war on their behalf.

Anti-Semitic Claims

This leads to another theme that people have claimed throughout history, the allegation that the Jewish people do not work for what they have earned. Historically, there has been an aversion to the Jewish people because of their institution of usury, or money lending with interest. [6] Usury, as it is called pejoratively, was a necessary institution for the Jewish people as a means of safeguarding their resources from a population that consistently harbored ill will towards them. It was also a means of making a living, in a time when the Jewish people were restricted from most trade professions. Because of these circumstances, anti-Semites like Henry Ford have made assertions like, “More than any other race he exhibits a decided aversion to industrial employment, which he balances by an equally decided adaptability to trade.”[7] Through the lens of an anti-Semite, the Jewish people are lazy, greedy, immoral people that actively try to cause harm to Christians; conniving people always engaging in a conspiracy against the good people of the world. While simultaneously being as Ford put it, “The world’s enigma”[8] Ford held this position because despite the Jewish history of being oppressed there were many success stories that would be utilized to propagate even more anti-Semitic claims. Such views are inexcusable, unfounded, and bigoted, and should be rejected especially in the modern world with “enlightened” people. However, it has been a common view held by countless millions of people throughout the Western world and beyond; antisemitism, or “blaming the Jew” has become as much of a tradition as the global participation in the Olympics.

Anti-Semites will use any excuse there is to blame the Jewish people in times of social unrest. In times where there is no rational excuse, they just fabricate one from thin air. They are even willing to invoke the supernatural to justify their hatred. Henry Ford, for example, can thinly veil his antisemitism when he wrote in, The International Jew, “Unless the Jews are super-men, the Gentiles will have themselves to blame for what transpired …”[9] In this instance, Ford again, claims that Jewish people were manipulating the system to make money from the backs of the common (hard-working) American people and refrain from participating in honest work. Again, this goes to the conspiracy mindset, but the other aspect that anti-Semites allude to is that the Jewish people are somehow agents of Satan. [10] Being a public anti-Semite, one would think that people would reject purchasing Ford’s automobiles; that people would institute a boycott. This, however, was not the case, Ford’s industrial fortitude along with his creation of the assembly line is firmly chiseled in the historical record as great deeds, with very little mention of his antisemitism.

This brief history of antisemitism should put into context the misguided notion that an anti-Semite may have for the possibility of Jewish people bleeding Christians to make religious delicacies or as it is commonly known: “Blood Libel.” The concept of Blood Libel predates the Strasbourg Massacre and the claims that the Jews poisoned wells and purposefully spread the plague. [11] In Robert Weinberg’s book, The Blood Libel in Eastern Europe, Weinberg chronicles varying cases of alleged Blood Libel. Weinberg’s findings go in lock step with what one may have deduced from the facts surrounding the religious ritual. Regarding the Catholic Churches’ position, Weinberg references Joshua Trachtenberg’s, The Devil, and the Jews: The Medieval Conception of the Jew and Its Relation to Modern Anti-Semitism, he wrote:

Church officials in Rome issued numerous papal bulls that rejected the notion of blood libel, asserting that Jews did not engage in Host desecration or use gentile blood for the baking of matzo. But the Vatican had difficulty stemming the belief among parishioners and clergy, particularly during the Passover and Easter holidays. The disappearance of a child was often sufficient to raise the cry of ritual murder, and if the child’s body turned up bruised or mutilated, Jews would be arrested, tortured, and even executed by local authorities.[12]

The Murder in Polná

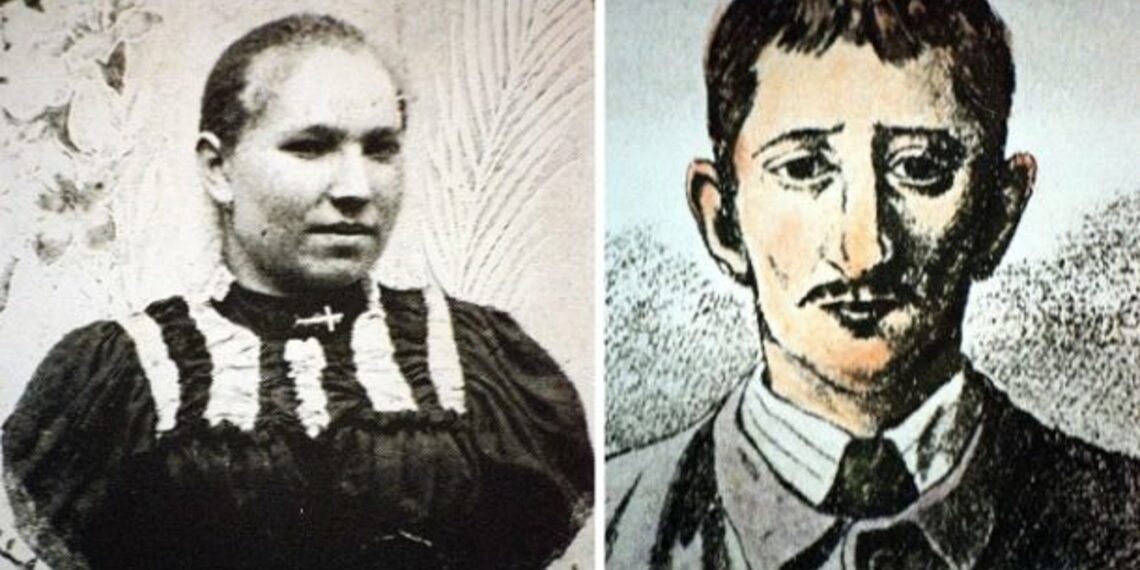

Weinberg’s analysis covers a macro view of the alleged phenomena and excludes the individuals who were harmed in its propagation. “The Hilsner Affair” also known as, “The Murder in Polná,” is a case that was made famous in part by how the criminal justice system failed in its operations. An unusual murder took place in the small village of Polná, Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic). On the twenty-ninth of March, in 1899, Anežka Hrůzová, a nineteen-year-old seamstress, left the village of Polná to return to her family’s house in Věžnička, only two miles away. [13] Three days later, Hrůzová was found battered with torn clothes near blood-stained rocks. She lay in the forest with her throat cut in a small pool of blood with a rope nearby; authorities were left with investigating whether or not the rope was used to drag the body to that isolated location, or if it was used as a murder weapon. [14] Unfortunately, the police in the late nineteenth century were more concerned with where Hrůzová was killed and not who the culprit was. The fact that her throat was slit and that there was not a lot of blood left on the scene, led the police and the people of the region to the conclusion that a Jewish person had to be responsible. Moreover, they concluded that Anežka Hrůzová was abducted somewhere else, then her throat was slit-like an animal, and she was then drained for her blood as an ingredient for consumption in a Jewish, Passover delicacy; her body was then discarded in the woods. [15]

As one may expect, Hrůzová’s body was examined to determine any motives outside of the Blood Libel hypotheses. The examiners identified that the cause of death was a laceration across the neck in a diagonal motion running from right to left; the blade dug in deep enough to hit the spinal column, indicating that the aggressor was much larger and dominating. They also found evidence that Hrůzová was struck several times in the back of the head, with strangulation marks around her neck, and several piercing wounds throughout her body. The examiners concluded with the declaration that her hymen was still intact, ruling out the motive of rape. [16] The team of examiners also concluded that Hrůzová’s body was still filled with blood; meaning that she was not bled to death. [17]

“The excesses to which several hundred residents of Polná joined in after Hilsner’s arrest— the windows of every Jewish residence were smashed— were more of an annoyance than a truly unsettling state of affairs, and even the Czech dignitaries in the area initially avoided taking a clear stand. “I don’t believe that there is ritual murder,” Mayor Sadil lied, and when Dr. Prokesch, the medical examiner in charge of the case, was asked about the alleged “bloodlessness” of the victim, he replied, “We are, of course, living in the nineteenth century.”[18] Proving that the population at large was seemingly waiting for an opportunity to lash out against the minority population. Not only was an innocent Jewish person to be wrongfully accused, but then people that did not even know him would pay the price of violence and vandalism.

Despite this evidence, the local authorities were still of the opinion that Hrůzová’s murderer was Jewish, and that the criminal’s motive was to obtain her blood. Being that she was a virgin helped her pursue this faulty logic. “The sheriff investigating the case was suspicious of four men who had been seen in the vicinity of the forest three days earlier. One of the men was 23-year-old Leopold Hilsner. He had a habit of walking in the forest in the area where the body had been discovered, and he had no alibi. What clinched it for the investigators, though, was the fact that Hilsner was Jewish.”[19] The police questioned local citizens about each of the four men in question. They were unable to give any substantial information about three of the four, but regarding Leopold Hilsner they identified him as an unlikeable, illiterate, unemployed Jew, that loitered the forest area where Hrůzová was found.[20] The journalist, Gustav Touzil, who was also the editor-in-chief of two local newspapers spread the notion of Blood Libel from the rural villages to cities outside of Bohemia. “To where, then, did poor Anezka’s blood disappear? … and this pure, innocent blood cries out to heaven for vengeance.”[21]

The police found that Hilsner resided in the basement of his widowed mother’s house in the Jewish community next door to a seamstress.[22] He was promptly incarcerated and put in jail pending his trial. Over the duration, “Journalists described Hilsner ‘as an unkempt, unshaven, dark stranger, who was simultaneously sinister (black), deformed (hobbled) and effeminate (knock-kneed and unable to grow a beard).’”[23] There is also a record of Hilsner being “of low intelligence” and being “sub-average intelligence.”[24] Several sources elude to Hilsner’s lack of intelligence in this polite manner. The case was before the intelligence quotient test was created, so there are no medical records confirming this account. People did not understand mental disabilities and autism as we do today; it can be suggested that Leopold Hilsner may have had such disabilities. This description of Hilsner was contrary to what the police had expected, they were looking for a large man as per the examination results of Hrůzová’s body.

Hilsner became frightened when he was told by fellow inmates and guards that gallows were being erected for his execution, even though he had not been sentenced; the trial was still pending. Likely, the inmates were purposefully harassing him for their amusement. The potentially disabled man was manipulated to confess that he did kill Anežka Hrůzová in the forest in Polná, on the twenty-ninth of March, in 1899. Under duress, he also confessed that he was aided by his two Jewish friends, Solomon Wassermann, and Joshua Erbmann.[25] This false confession would explain how a frail young man such as Hilsner, was able to commit such a heinous crime. Visually it was obvious that Leopold Hilsner was not physically capable of beating Hrůzová or inflicting the deadly wounds throughout her body without the help of bigger men. Hilsner was under the assumption that if he confessed, his life would be spared, and he would receive a more lenient sentence. He was told this by the inmates that were harassing him. The police investigated Wassermann and Erbmann only to find that they had credible alibis and could not have assisted Hilsner with Hrůzová’s murder.

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Hilsner was defended by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (T.G. Masaryk), who was a professor at the Bohemian university of Prague at the time. Masaryk would later become the chief founder and first President of Czechoslovakia between the years 1918 and 1935.[26] Masaryk was always an advocate for the Jewish people even during periods of extreme antisemitism. Regarding the Hilsner affair, he said, “I decided to defend Hilsner because the man was innocent. I was also concerned about the honour of the Czechs. I’m called a traitor to the nation because I couldn’t bear its disgrace… What would the world think of the culture of our nation, if the Jews, who had been living with us for centuries, could remain cannibals as they allegedly were, according to those in our nation who spread the myth of ritual murder?[27] Despite Masaryk’s best efforts, Hilsner was found guilty of complicity in the murder at the court in Kuttenburg by the prosecution led by Scledder-Swoboda and Dr. Baxa. The Hilsner trial was sent to a superior count that proceeded in the same manner. Hilsner was openly accused of cannibalism in the courtroom and found guilty of complicity to murder at the Court of Cassation at Vienna one year later in October 1900. [28]

“As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.”

While Hilsner awaited his death sentence, a second body was later found in the same place. Maria Klima was a servant who went missing on July 17th, 1898 (over 8 months before Hrůzová’s death). The facts in this second murder charge became muddled when “The proceedings were a major judicial and journalistic event; close to 150 witnesses were brought in. The hearing went on for seventeen days and filled up hundreds of newspaper columns … The Hilsner case was a harbinger of things to come, and it stayed in the collective memory even after Kaiser Franz Joseph— in response to the sensation the case made throughout Europe— commuted the death sentence to life imprisonment.”[29]

“Complicity to murder” means that Hilsner was involved and was working with others. Even though the two mystery men were identified as innocent in the previous trial, the courts accepted the alleged witness’ testimony, and Masaryk was portrayed as a fool for attempting to defend the hopeless Jew. This case informed Masaryk’s ideology and drove him to continue to be an advocate for Jewish people. There was no mistake that Czechoslovakia and many parts of Europe were plagued with an active and long-standing sentiment of antisemitism. Even though Masaryk had lost the case for Hilsner, he advocated for his release to varying government officials including the ultimate authority of the Kaiser. On March 24th, 1918, Masaryk’s efforts were vindicated when Emperor Karl I, pardoned Leopold Hilsner. The emaciated and frail Hilsner died at the age of fifty-two on January 9th, 1928.[30]

The Jewish Telegraph Agency wrote an article about this case in response to Hilsner’s death three days later. The article titled, Leopold Hilsner, Tragic Figure in Ritual Murder Accusation Case, Dies, summarized the injustice against Hilsner by the local townspeople. The article stated, “Those who at the first trial had spoken of a knife which they had seen in Hilsner’s possession, now asserted distinctly that it was such a knife as was used in ritual slaughtering. The strange Jews who were supposed to have been seen in company with Hilsner were more and more particularly described… The verdict pronounced Hilsner guilty of having murdered both Agnes Hruza and Maria Klima. He was sentenced to death on Nov. 14, 1900, but the sentence was commuted by the emperor to imprisonment for life.”[31]

Quickly after Hilsner’s pardon in 1918, Masaryk became the first President of Czechoslovakia, and he was a founding member in writing their Constitution. “The Constitution of the First Czechoslovak Republic was the first in the world to recognize the Jews as a separate nationality. With the government support, government national Zionist congresses took place in Czechoslovakia (1921, 1923, and 1933).”[32] It was Masaryk’s goal to aid the Jewish people in establishing a Zionist State so that they could be safe from their antisemitic neighbors.

The Hilsner affair seems unusual to us in the twenty-first century in the United States, but cases of “Blood Libel” were seen all over Europe during the nineteenth century. Unexplained disappearances and murders had become such a common event throughout Europe in the late 1800s that the police were grasping at any excuse to solve the cases. “Blaming the Jew” had become an effective answer. There are over a dozen cases that resemble the Hilsner Affair between 1894-1899, Many historians believe that the Dreyfus Affair had emboldened people in their antisemitism. This rationale can be justified in how the Czech citizens began vandalizing innocent Jewish establishments after it became public that Hilsner was the suspect in the murder in Point. Examples of this can be found in Konitz in Prussia (modern-day Poland), Kyiv Ukraine, and Xanten in the Prussian Rhineland. “In Xanten, townsmen found the body of a five-year-old boy whose throat had been slit. The body, it was said, had been drained of blood—evidence that pointed to the Jews, and especially to the kosher butcher Adolph Buschhoff… Such “evidence” proved sufficient to jail Buschhoff and provoke a chorus of anti-Jewish condemnation from the local and national antisemitic press, including Catholic and conservative newspapers, increasingly antisemitic at the end of the century.”[33]

Hillel J. Kieval, the Professor of Jewish History and Thought at Washington University in St. Louis, claims that the Czech’s antisemitism was firmly found in racist sentiments that were commonplace throughout Europe. Kieval cites that Hilsner’s skin tone was “dark” with the implication that his mistreatment may have extended passed his Judaism. [34] Kieval comes to this conclusion from reading contemporary authors of the era like Thomas Timayenis: a fervent anti-Semite who wrote, The American Jew, in 1888. Timayenis’ book makes claims that Jewish people are less than human, and he supports these claims by noting imagined exaggerated physical differences. Timayenis labeled Jewish people as “Vampires” and likened them to rodents throughout his marathon of antisemitic allegations. [35] If Kieval is right, then the injustices against Hilsner were due to his racial differences more so than his religious practices. Regardless of the justification for the mistreatment of Leopold Hilsner, the inspiration was found in antisemitism.

One of the difficulties in researching nineteenth-century case studies of antisemitism is that the people of the time seem to have treated them as non-events. Many of which were not properly recorded and others were simply disregarded. Edward Berenson refers to these cases in his book, The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town. Berenson makes it very clear that what happened in Polná was not uncommon, he wrote, “Each of these cases, and several other smaller ones resulted in widespread violence against Jews. There is no need to fully narrate each accusation; the story, with just a few modifications and local details, is always the same.”[36]

Blaming Jews for famine, drought, economic depression, war, murder, and widespread illness, is a historical trend that can be found in any era because antisemitism is as old as the historical record itself. In every generation there are different excuses to blame the Jews; during the Roman Empire, it was the Christ Killer excuse, in the medieval era it was for religious rituals like Blood Libel, before the enlightenment it was because they were segregated and accused of being secretive, during the enlightenment it was because they were not respected as citizens, after the enlightenment it was racial, then it became economic. The antisemitic elephant in the room of course is the Holocaust, the attempt to systematically liquidate an entire race. This trend has led many people to question, where does the always-changing source of antisemitism come from?

“As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.”

In the book Ordinary Men: Police Battalion 101, Christopher Browning’s position contradicts Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s notion that the German people were inherently evil; that they were looking for an opportunity to strike back against the Jewish people for the results of World War I and the conditions under the Treaty of Versailles. The thesis of Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, claims that antisemitism was such a large part of the European culture that the average citizen did not need much motivation to commit the horrific crimes against humanity.[37] However, Goldhagen is wrong, and he can be empirically proven wrong by Christopher Browning. At the beginning of Ordinary Men, Browning writes about Major Wilhelm Trapp, a commander of Reserve Police Battalion 101 (the battalion that the book focuses on), and how he has difficulty giving orders to his men. The men of the Police Battalion are those who were not fit to be in the SS or the German military. These men were either too old or had some ailment but still wanted to serve. Browning writes, “Pale and nervous, with choking voice and tears in his eyes, Trapp visibly fought to control himself as he spoke. The battalion, he said plaintively, had to perform a frightfully unpleasant task.”[38] Major Trapp asked his men if they agreed with the orders, to which many of them said, ‘No, Herr Major!’[39]

If the tasks given to the battalion were unpleasant to them, then how could it be in their nature to commit such atrocities? To further prove the point that the Germans and other Europeans were not inherently predisposed to murder, Browning reveals that Trapp told his men that if they were not comfortable with the orders, they could leave the battalion, which many of them did. There is also proof that up to twenty percent of the battalion members that stayed would shoot in the air or at the tree line instead of aiming for what was supposed to be their targets.[40] What is concerning, however, is the percentage of people that went along with the orders and those that acted heinously without being ordered to do so. Browning’s work tells us that antisemitism is not a genetic trait; moreover, it is a societal condition. If one is an optimist, this understanding can be presented as good news, it means that if people construct a more tolerant society, that antisemitism and anti-Semites can become a thing of the past.

Such a notion is aspirational, but it is not a reality that exists today. The Jewish people continue to be scapegoated for social ills around the globe. Anti-Semites rationalize their hatred with imaginary facts and misinformation, much like the Blood Libel cases of not so long ago. The festering hatred against the Jewish people for religious and racial differences is stoked by anti-Semites throughout history: Pontius Pilate, Martin Luther, T. Timayenis, Gustav Touzil, Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and Adolf Hitler are but a few of the screaming voices that echo through the annals of history. With knowledge and understanding of this cruel history, there is hope that one day people will learn to grow deaf to the screaming bigots of the past and focus on a future that neither wants nor needs scapegoats.

PowerPoint

References

Berenson, Edward. The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, independent publishers since 1923, 2019. Print. 70-5. Berenson examines a variety of different Blood Libel cases in proximity to the Hilsner Affair. He states, “Each of these cases, and several other smaller ones, resulted in widespread violence against Jews. There is no need to fully narrate each accusation; the story, with just a few modifications and local details, is always the same.”

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. Print. Browning examines the actions of a Police Battalion during World War II. He concludes that there were many anti-Semites throughout Europe who was anxious to act against the Jewish people, however, there were also many who would rather not. Meaning that not all Europeans were antisemitic.

Ford, Henry. “The International Jew.” The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History. 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 570-72. Ford presents the Jewish people as a fragile race of people, while simultaneously being economic juggernauts. His views are thinly veiled but antisemitic, nonetheless.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler’s Willing Executioners. New York: Random House, 1997. Goldhagen’s thesis is that the Europeans before World War II were looking for a reason to attack the Jews. He claims that Hitler gave them such an excuse and they were grateful for the opportunity.

Kamins, Toni L., Gabe Friedman, Raffi Wineburg, and Julie Wiener. “Leopold Hilsner, Tragic Figure in Ritual Murder Accusation Case, Dies.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, January 12, 1928. https://www.jta.org/1928/01/12/archive/leopold-hilsner-tragic-figure-in-ritual-murder-accusation-case-dies. This Jewish paper recorded Leopold Hilsner’s pardon in 1928. The JTA offers a primary source from the people of that era.

Kieval, Hillel J. “Representation and Knowledge in Medieval and Modern Accounts of Jewish Ritual Murder.” Jewish Social Studies, New Series, 1, no. 1 (1994): 52-72. Accessed February 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4467435. Hillel J. Kieval, the Professor of Jewish History and Thought at Washington University in St. Louis, claims that the assault against Hilsner was more racial than religious.

Laqueur, Walter. The Changing Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times to the Present Day. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Laqueur notes that many Christians falsely accuse the Jewish people of the death of Jesus Christ.

Lindbergh, Charles A. “Who Are the War Agitators?” Speech, September 11, 1941. Lindbergh attempted to rile the nation against the Jewish people around the time when the United States joined the Allied powers in WWII. He claims that there was a conspiracy propagated by the Jews and the Roosevelt administration to get the American people to join a war that was against their best interests.

Naillon, Erin. “The Mystery Behind the Hilsner Affair.” CitySpy Network // Czech Republic / Prague, March 29, 2018. https://cz.cityspy.network/prague/features/the-mystery-behind-the-hilsner-affair/. Naillon reports the facts behind the Hilsner affair concisely with no commentary.

Nohl, J. “The Black Death and the Jews.” The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History. 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1-4. A literary perspective of anti-Semites during the Black Death. A call to arms against the Jewish people resulted in the Strasbourg massacre of 1349.

Pojar Miloš. T.G. Masaryk and the Jewish Question. Praha: Karolinum Press, 2019. A synthesized history of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (T.G. Masaryk), the defense lawyer for Hilsner in his trials who would later become the first president of Czechoslovakia.

Stach, Reiner. Kafka: The Early Years. Princeton University Press, 2017. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv7h0tx4.15. A detailed reporting of anti-Semitic journalism in the ninetieth century.

Timayenis, T. T. The American Jew: An Expose of His Career. Minerva Publishing Co., 1888. A primary source of antisemitic beliefs. Timayenis makes racial claims against the Jews and seeks to prove that they are inferior and should not be trusted.

Weinberg, Robert. “The Blood Libel in Eastern Europe.” Jewish History 26, no. 3/4 (2012): 275-85. Accessed February 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23352438. Weinberg references Joshua Trachtenberg’s, The Devil, and the Jews: The Medieval Conception of the Jew and Its Relation to Modern Anti-Semitism; Weinberg’s synthesis of Trachtenberg’s work concludes that the Church was against notions of Blood Libel. The Church sought to end the archaic belief that the Jews were engaging in cannibalism.

End Notes

[1]. Edward Berenson. The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, independent publishers since 1923, 2019). 75.

[2]. Walter Laqueur. The Changing Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times to the Present Day. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). 48.

[3]. J Nohl. “The Black Death and the Jews.” The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History. 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1.

[4]. J Nohl. 3-4.

[5]. Charles. A. Lindbergh. “Who Are the War Agitators?” Speech, September 11, 1941.

[6]. Walter Laqueur. 155.

[7]. Henry Ford. “The International Jew.” The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History. 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 570-72

[8]. Henry Ford. 571.

[9]. Henry Ford. 572.

[10]. Walter Laqueur. 55.

[11]. J Nohl. 1-4.

[12]. Weinberg, Robert. “The Blood Libel in Eastern Europe.” Jewish History 26, no. 3/4 (2012): 275-76. Accessed February 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23352438.

[13]. Erin Naillon. “The Mystery Behind the Hilsner Affair.” CitySpy Network // Czech Republic / Prague, March 29, 2018. https://cz.cityspy.network/prague/features/the-mystery-behind-the-hilsner-affair/.

[14]. Erin Naillon. 1.

[15]. Miloš Pojar. T.G. Masaryk and the Jewish Question. (Praha: Karolinum Press, 2019). 96.

[16]. Hillel J. Kieval. “Representation and Knowledge in Medieval and Modern Accounts of Jewish Ritual Murder.” Jewish Social Studies, (New Series, 1, no. 1 (1994): 52-72. Accessed February 23, 2020) www.jstor.org/stable/4467435. 53.

[17]. Toni L Kamins., Gabe Friedman, Raffi Wineburg, and Julie Wiener. “Leopold Hilsner, Tragic Figure in Ritual Murder Accusation Case, Dies.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, January 12, 1928. https://www.jta.org/1928/01/12/archive/leopold-hilsner-tragic-figure-in-ritual-murder-accusation-case-dies.

[18]. Stach Reiner. Kafka: The Early Years. Princeton University Press, 2017. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv7h0tx4.15.

[19]. Erin Naillon. 1.

[20]. Hillel J. Kieval. 53.

[21]. Hillel J. Kieval. 64.

[22]. Hillel J. Kieval. 53.

[23]. Edward Berenson. 75.

[24]. Erin Naillon. 1.

[25]. Erin Naillon. 1.

[26]. Miloš Pojar. 150.

[27]. Miloš Pojar. 125-6.

[28]. Toni L Kamins., Gabe Friedman, Raffi Wineburg, and Julie Wiener. “Leopold Hilsner, Tragic Figure in Ritual Murder Accusation Case, Dies.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, January 12, 1928. https://www.jta.org/1928/01/12/archive/leopold-hilsner-tragic-figure-in-ritual-murder-accusation-case-dies

[29]. Stach Reiner. 167.

[30]. Erin Naillon. 1.

[31]. Jewish Telegraph Agency. (1928).

[32]. Miloš Pojar. 248.

[33]. Edward Berenson. 74.

[34]. Hillel J. Kieval. 65.

[35]. T. T. Timayenis. The American Jew: An Expose of His Career. Minerva Publishing Co. (1888).

[36]. Edward Berenson. 74.

[37]. Daniel Jonah Goldhagen. Hitler’s Willing Executioners. New York: Random House, 1997.

[38]. Christopher R. Browning. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. (New York: HarperCollins, 1992) Print. 2.

[39]. Christopher R. Browning. 58.

[40]. Christopher R. Browning. 130-1.

Courses

Courses America and the World

America and the World East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present

East Asian Modernization: 1600 – Present Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Introduction to Holocaust and Genocide Studies